CTRL – Rethinking Cultural Assets, De-Capitalising Intellectual Property. A New Comprehensive Approach to the Music Market. An article by Margherita D'Andrea and Corrado Gemini as published in the Transnational Dialogues Journal 2016.

Summer 2016: the heat is oppressive as you book your house by the sea on Airbnb. You managed to organise seven special days of holiday.

After having filled all the places in the car with passengers who will share the cost of the journey with you, thanks to BlaBlaCar, you rush to prepare dinner for the Norwegian who’s passing through and will stay in your house next week while you’re away.

Yesterday you published on Spotify and iTunes your most recent album: you quickly check the feedback as your manager calls you. “Are you leaving? The vinyls on BigCartel are selling fast, and the new track is at number four on Beatport! Remember, finish off those last two tracks of the album by next week, because then you’ll be starting work again and you won’t have any more time!”

Suddenly a thought comes to mind and you turn to stone.

“I’ve got such an incredible amount of tools that make possible this horizontal type of economy, putting me in contact and allowing me to work directly with others like me, with the same interests in common, in an environment in which, however, I’ve got no way of going beyond.”

The decision processes behind these tools, that have taken life thanks to my own use, are in fact completely beyond my control.

Red pill or blue pill?

Red pill: tomorrow you wake up and you continue to believe that the management of work and economic dynamics will always be beyond your reach.

You stop asking yourself why you cannot self-organise, despite the fact that today you have the tools to do so, and you continue to be a user, client and consumer for the service companies managed by others.

You life continues in a position of subordination, as you have known your whole life up until now.

If then you are the front-person of Portishead, and you receive an annual pay from streaming, you think the problem is music being sold at a low price, and you get annoyed[1].

Blue pill: you take control of the tools you have at your disposal. You found a cooperative in which all the members have the same power, and together, on equal-footing, you manage these tools, deciding the releases, optimising the streams, constantly working to break down the barriers between providers and clients, between management and use, between administrator and employee.

Your life changes radically: it is now characterised by a diffused responsibility within the sector in which you participate, and within a community in which you collaborate, equipped with shared means and shared tools.

These experiences make you re-think not only your professional position within the market, but indeed the whole idea of what work is.

Right now, the blue pill is the challenge that is stirring a global community of producers of art, culture and performance, who have up until now always been subjugated to their respective industries.

The collective ownership and management of the platforms of production, distribution, and cooperation in general, is the way to create a cultural sector in which there is an equal relationship between practitioner and user. At this historical moment in time we can see the possibility to concretely realise a different way, thanks to new technological tools, as well as the will to change that the crisis of recent years has generated, it is a burning question more now than ever before.

To focus on the music market, which is indeed the most monopolised cultural sector of all, with just three companies controlling 70% of the world market, we can see that the evolution of production tools and the arrival of online platforms have with time led to a complete liquidisation of the sector linked to an (old) industrial model.

From a rigid system of roles, we are moving towards a model in which practitioners have multiple roles: today it is not easy to find a record company which does not also deal in organising tours for their artists, a radio that does not organise festivals, or a label that does not also take care of merchandising.

A market which needs to simplify necessarily means also a reduction in the number of intermediary positions: we are living through a huge liquidisation fixed on beating prices down, and the figures in power within the old system are trying to survive by maintaining as much of the market shares as possible.

Production costs have fallen and workstations are evermore available, to the point that recording studios are being used only for the final phases of recording for an album. Distribution has also been revolutionised by the liquidisation of music: the physical media (CDs and vinyl) have become collector items, while everyday music is accessed via private streaming platforms (Spotify/YouTube), which have lowered the profits that artists can get from selling their music. Communication and promotion have radically distanced themselves from their traditional professional sectors with the explosion of global social networks and large aggregators (Facebook/Soundcloud), reaching out directly from the hands of the artists or their collaborators.

The diminishing of distance between the author and the public facilitated by social networks has led to financing straight from the supporter to the artist. As of today platforms such as MusicRaiser represent an important part of the budget in the sustainability of many artists, from the independent circuit to the mainstream (an Australian metal group asked their fans to give them an annual work pay through a crowdfunding campaign[2]).

The picture is pretty clear. The application of a virtuous model based on the common ownership of a platform by the authors and other practitioners works in this unprecedented moment of the market: relational fluidity, direct contact with the public, lowering of costs, equity in redistribution, improving the quality of production, the diffusion of culture outside of, or beyond, the logic of capitalism.

Right before our eyes there stands a new model for the music market, completely different to the industrial model, it is just up until now we had not really noticed.

CTRL has the aim of drawing attention to this new model and practising it through the cooperation of authors and other practitioners within the same legal body, as well as through an online platform.

By using de-centralised administration technologies (Blockchain) and digital democracy, a fluid market environment can be managed based on collective agreements, while in a constant process of revision of the governance that regulates it.

But that is not all.

Make music free

Another step forward to be made to bring about this change however, without which it is not possible to realise real horizontality, is the analysis of the current management model of Authors’ rights, on a legal level and within the market.

Intellectual property and the classification of goods according to the criteria of rivalry and excludability, as laid down in economic theory, simple are not a correct equation.

Music, by its very nature, is not based on rivalry or exclusivity; the listening to of a track by one individual does not limit the possibility for others to also enjoy it. Indeed, it is the opposite. When one listens to music, others are exposed, forming new audiences and interest. The creation grows in proportion with its diffusion.

This concept is a common development in the artistic expressions of musicians who increasingly work together, especially in digital media, and in some modern non-Western societies which are culturally connected to the idea of natural, collective artistic creation. It is an idea also shared in areas where tradition still plays a central role, and the concept of the public domain of the immaterial is as common as it is considered essential in the transmission and development of local arts and culture.

The idea of the individual appropriation of artistic creations was unknown in certain parts of South Africa and Brazil before the first arrivals of the new colonisers, the Western multinationals indirectly responsible for the ‘Free Trade Agreements’, which saw the arrival of a new kind of development from the 1990s onwards.

Following the global logic of the rule ‘one law fits all’, these agreements focused on constructing a national and international rules system regarding intellectual property, based on the standards of the most economically advanced countries.

This led to the establishment of the TRIPS (Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights[3]) in 1994, designed to regulate aspects of intellectual property rights relating to trade, whilst also encouraging ad hoc legislation and penalty systems in countries where they did not already exist.

Article 63 of the Agreement exemplifies a typically commercial understanding of music; it is a tool for the accumulation (long-term or indefinitely) of repertoires, with restrictive effects on the circulation and distribution of works. The article in fact refers to the resolution procedures for disputes which are already built into the WTO: an example of a rule able to exclude completely, or in part, national jurisdictions, leaving it to the International Arbitration Court to resolve disputes and interpret all the agreements that fall within the area of copyright.

From an economic-political perspective, such a model (which today sees the TTIP negotiating other fundamental building blocks) imposed significant historical changes: domestic courts lost many of their powers; there was the submission of power/duty regarding copyright laws to an arbitration control greatly influenced by the voices of the majors; there was a freezing of the autonomous power to legislate (called the ‘Regulatory chill effect’) by individual States who wanted to make reform in the area, to point which there were real sanction and compensation procedures for those States which had legal provisions that were not uniform and did not conform, which could thus be potentially harmful in terms of foreign royalties, held by the same multinationals.

Such a stubborn operation of control is evidently due to an awareness of a danger at its theoretical core. Indeed, as Jessica Litman wrote in her article ‘The Public Domain’, “it is our inability to trace or verify the lineage of ideas that makes it essential that they be preserved in the public domain”[4].

Authors’ rights were born with the intention of allowing the sharing of artistic creation while safeguarding at the same time the individual rights of the authors. They were not created to be used as a dividable, marketable token which aims to capitalise on repertoires, time after time.

The accumulation of vast repertoires by record companies through buying Authors’ rights contractually, added to the copyright law that has always been in the hands of the big companies, and the continued rise in temporal terms of protection of the work, all come together to paint a worrying picture for the future, in which there will no longer be any source of culture truly in the public domain, with disastrous consequences that are not difficult to imagine.

The current system seems to be more interested, however, in protecting the rights of the large intermediaries, as the cases of Sixto Rodriguez testify (see the Oscar award-winning documentary ‘Searching for Sugar Man’), as well as many of the recent cases that have plagued platforms such as SoundCloud. The solution can only be radical.

It is necessary to re-think and re-construct not only the evermore physically-free modes of production and distribution, but also the way in which we protect those rights, that must take into account the opportunities that new tools can give us, both in terms of the growth of collective consciousness, as well as in terms of productive resources and relational networks.

In this sense, thanks to their modularity and adaptability, the Creative Commons licenses feed a virtuous system because they define a space for sharing and global use in a network of potentially infinite knowledge.

Paul Krugman, in an interview by the New York Times in 2008, said, “bit by bit, everything that can be digitized will be digitized, making intellectual property ever easier to copy and ever harder to sell for more than a nominal price. And we’ll have to find business and economic models that take this reality into account”[5].

Only by returning to a more mutualist, and less competitive, conception of Authors’ rights, or by de-merchandising and undoing the closed logic of copyright, will it really be possible to give life to the change we want to see.

The great challenge that Creative Commons are called to work on in the whole system of music production is precisely that of being able to have a real impact on the market, and the way to do it is to build, on an international level, a collective body which deals with the safeguarding and management of Authors’ rights, for those who choose to use these licenses.

The creation and promotion of a Collecting Society based on the Creative Commons licenses, managed directly by the authors, is for this reason another fundamental aim of CTRL.

CTRL is a process born from the very particular context of Italy, which has facilitated its conception and is accelerating its realisation through networks of workers and activists. The short-term objectives are the opening of a production cooperative and the development of a web platform, as well as initiating the construction of a collecting society.

But this is an operation that involves the music market as a whole, and it is only with a solid base of theoretical and practical international cooperation that we can make real changes: researchers, economists, lawyers, activists, foundations, politicians, authors and workers in the market that are interested in contributing to this new pathway are invited to get in touch with the project developers and get involved in its active construction.

info@ctrlproject.org

Margherita D’Andrea is a lawyer and the co-founder of CTRL Project.

Corrado Gemini is a musician, photographer and the co-founder of CTRL Project.

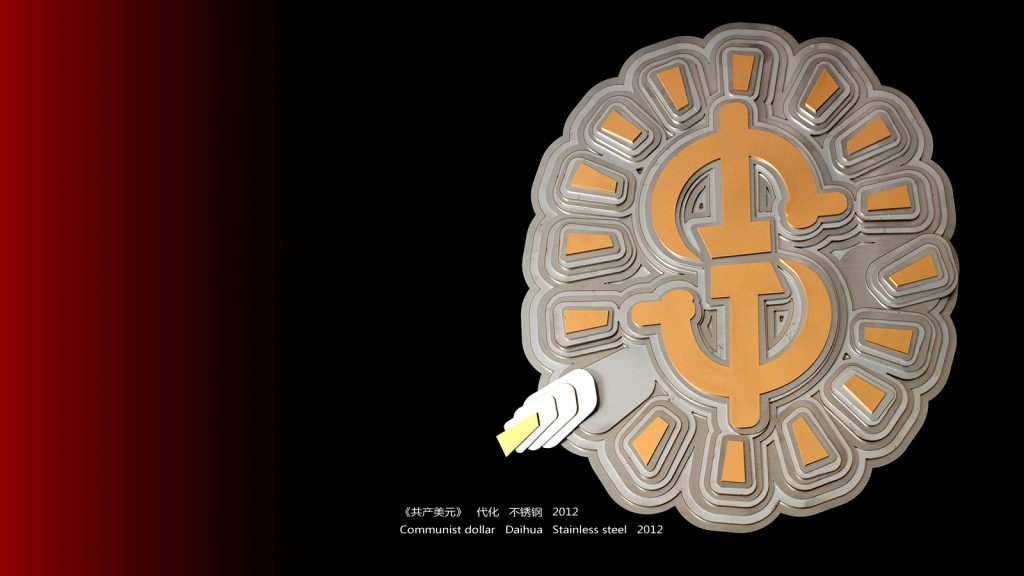

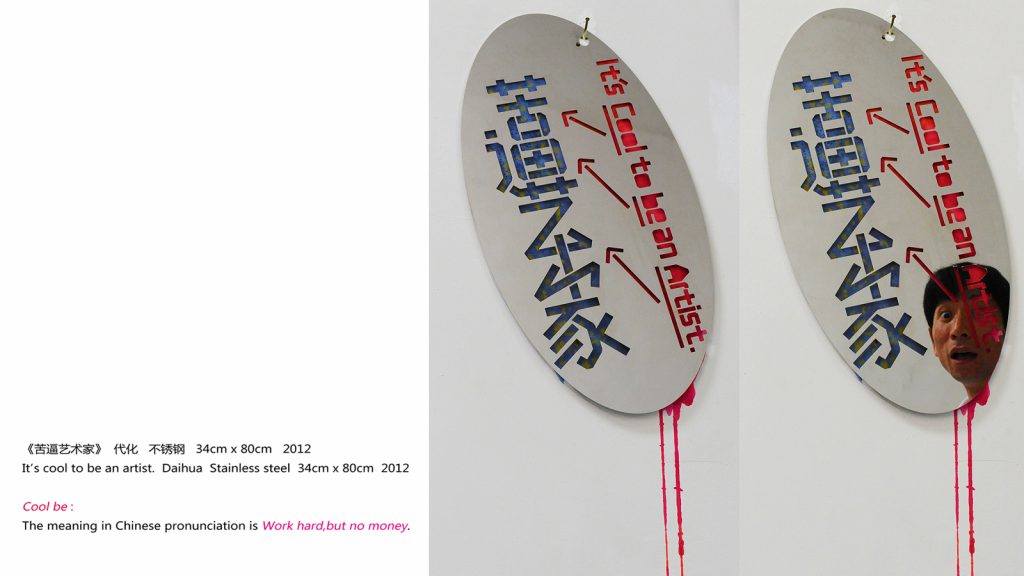

[All artworks are courtesy of Dai Hua 代化. Cover image: 我顶我倒 (Birth and Destruction), 2008, detail]

[1] https://twitter.com/jetfury/status/587744520403607552

[2] https://www.patreon.com/neobliviscaris

[3] https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/27-trips.pdf

[4] https://law.duke.edu/pd/papers/litman_background.pdf

[5] http://www.nytimes.com/2008/06/06/opinion/06krugman.html?_r=0