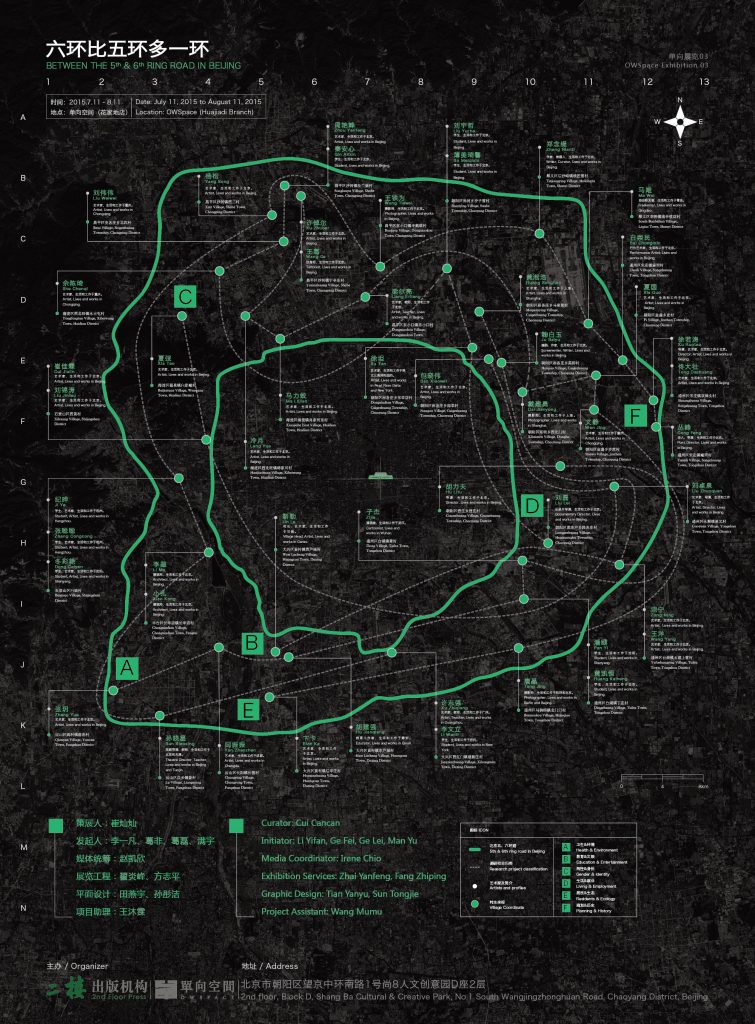

This is a survey project started by the publishing house Floor #2 Press and conducted by artists in the administrative villages within the fifth and sixth rings of Beijing. The project invited and welcomed each participant to conduct field surveys in an artistic form on one particular aspect of a selected village in the region, to be carried out independently or cooperatively with local people for a period of not less than 10 days.

Interview with Man Yu 满宇, Ge Fei 葛非 and Ge Lei 葛磊 by Luigi Galimberti 鲁及 and Ma Yongfeng 馬永峰, as published in the Transnational Dialogues Journal 2016

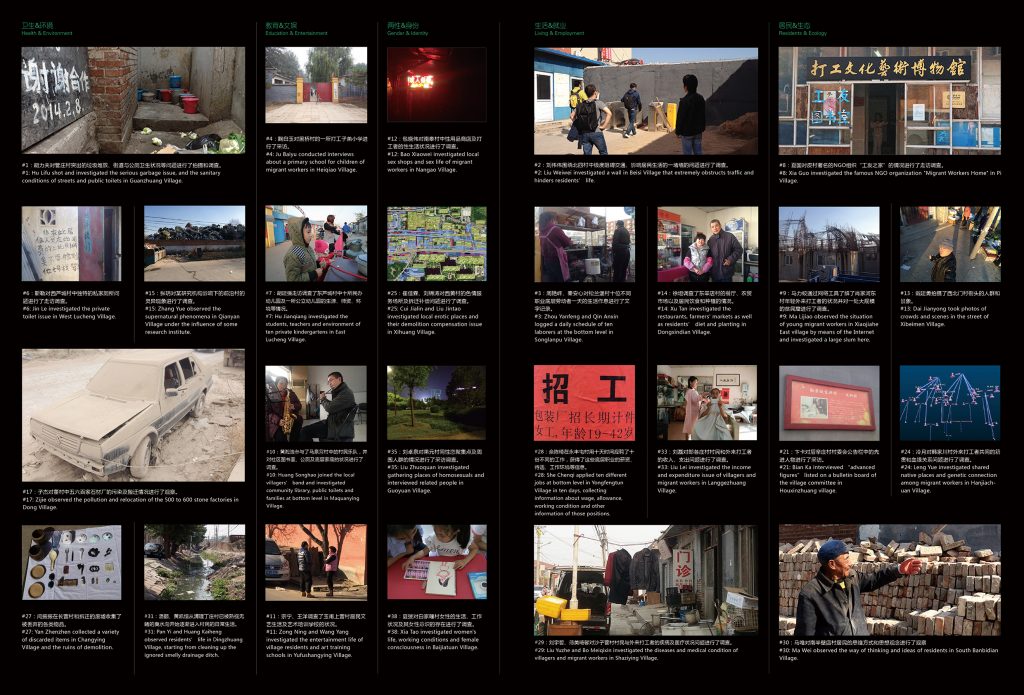

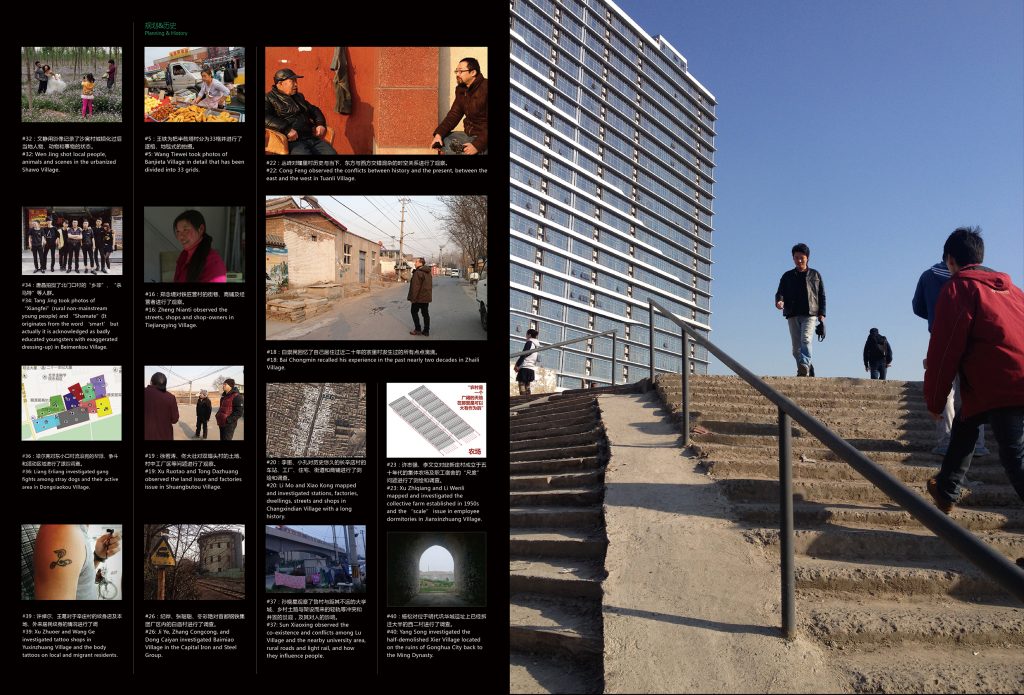

A total of 51 participants, made up of artists, film directors, writers, architects and designers, were divided into 40 teams, and each team chose an area of the selected village in which to do the surveys. The surveys covered subjects including food, hygiene, transportation, accommodation, education, entertainment and local customs, giving a comprehensive and rich view of the commonalities and variety in the region. The project has received a great deal of attention ever since, as many important media channels in China have reported on the project, giving more people the possibility to know about and understand this region. It has indeed inspired a new wave of site-specific works in Chinese contemporary art.

Question (Luigi Galimberti 鲁及 and Ma Yongfeng 馬永峰): Why did you start this project? Why was it so important to you?

Answer (Man Yu 满宇, Ge Fei 葛非 and Ge Lei 葛磊): We, the three of us, thought about working with Li Yifang, a teacher in Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, on a project about Chinese rural villages at first, because we were concerned with the subject of Chinese rural villages. Later we found that we were more interested in the relations between cities and rural villages, so we went to the villages surrounding Beijing in 2013, such as the village Pi Cun, to see what state the villages were in. We were shocked by what we saw. Then we went to Heiqiao village and many other villages. We wanted to see what they too looked like.

As we mentioned above, we were in Heiqiao village, where about 40,000 migrant workers from all over the country are gathered. The one to two thousand or so artists living there however, in the same village, had nothing to do with them; there was a river running between them. We thought that the artists were probably all working in their workshops and did not really understand the village at all. So we thought to invite the artists – and what we mean by “artists” here is in a broad sense, encompassing architects, musicians, dancers, etc. – to see the villages. We did not expect them to create works from the visits.

After that, we had many discussions and an idea began to emerge, that of a survey. Each artist had his own expertise and sees things from his own perspective, with his own interests, with different views regarding hygiene, education, etc. So there are issues relating to schools for workers’ children, transportation, labour security, medication, and the list goes on. In the end we divided the artists – 51 in total – into 40 teams to cover all the issues that had arisen.

Q: In the face of the increasingly fierce social conflicts or tension, as a publishing house, what role do you think artists can play?

A: During actual operations we found that artists basically couldn’t do anything. While on site, in fact, no one needs art or any artistic form, so we think when artists went to a village to explore and start their work, it was more about attracting people’s attention through the forms artists used, or the issues presented. So we thought one important point we were exploring was what artists can do in society, when art is cast as a subject.

We also emphasised a sociological approach. Although the surveys conducted by the artists had a sociological appearance, they were definitely different from those that would be conducted by sociologists; the results tended to be more vivid, specific and detail-oriented. For example, one issue explored was that of stray dogs – a sociologist wouldn’t investigate such an issue. Artists have certain ways – such as by exaggeration – to attract people’s attention and make the subject more visible.

Q: How do you define your work in this project? For the artists, the architects and others from different fields, what are their approaches in the relation between urban areas and villages? How do you position yourselves?

A: There were three requirements, if an artist were involved. One was that the artist had to live in the village for at least 10 days, depending on the artist’s individual situation. In fact, some of the artists lived there for over a month and some of them were staying there long term, and have continued working on the project. Every day we would broadcast their individual experiences live. Although we considered this project sociological, it was even more about individual experiences. It was about the events of individuals. So we expected a minimum of an 8-hour live broadcast every day. The last requirement was to prevent the artist taking the social site as a subject of art or treating it as a spectacle – as is the tendency in the specific context of Chinese contemporary art. To counter this, we required an investigative element to be included in the artists’ work. This requirement was more flexible. We stopped artists from returning to the way of thinking about “making art”, to doing work that would be directly related to the specific site. And since artists were creative by themselves, we thought it was good enough as long as the investigative elements were included. These were the three basic requirements.

Q: If it is a total failure or frustration for an artist when confronting society, should the artist enter society entirely, or how can he make a living through his art?

A: We think there are several reasons for an artist to return to society. The most important one is that there has been a crisis of practice in Chinese contemporary art – it does not have validity, and what we are trying to do is validate contemporary art in China – to see what artists can bring to society. That is a very important reason. Another reason is to do with the logic of contemporary art. Art has always been the practice of individuals, a response to the places where the artists are living, it is not something like a post-colonial product, or something about learning from others and copying styles, and then displaying the generated works in museums which have nothing to do with the real situation the artists are in. Also, I tend to oppose the so-called idea of “art enters society”, because art itself is a part of society, it doesn’t intervene with society, it has never been outside of society. To say that art has been something alien to society, and now it is entering society, reveals a certain concept of pure art. But pure art doesn’t really exist; art is part of the order of society. What is art? That is a question we shall be cautious about. Is it a practice distributed or given an ideology by society? We shall be cautious about that. What we offer now is some kind of retort to what art has been considered to be. In the beginning, when we started the project, we went through a certain process, then we thought that was not art, not something we could accept, and then later on we came to a common conclusion that what we were doing was real contemporary art, while what others were doing was not, theirs was mimicry. Besides, we were not aiming this work at an audience of “the art world”. And this brings us back to a basic principle: we have always thought that art should not intervene with social movements, but be part of them.

We should be able to reflect on our own behaviours.

Unless artists are forced into a corner, they cannot be part of society.

In China, artists are very narcissistic. They consider themselves elite, apart from society, which means they are accomplices of power. That is exactly what we oppose in the project that we have been doing; we oppose hierarchical society, since this is the root of unfairness and injustice.

Man Yu 满宇, Ge Fei 葛非 and Ge Lei 葛磊 are the founders of the non-profit publishing institution Floor #2 Press. Luigi Galimberti 鲁及 was the director of Transnational Dialogues (2012-2016). Ma Yongfeng 馬永峰 is an artist and curator. He is the founder of the collective Forget Art.

[Images by Floor #2 Press, Beijing; please get in touch in case you wish to re-use them]