Debates and reflexions from the Brazilian Caravan experience, part of the project Transnational Dialogues 2014. By Raphael Franco.

The XXI century has brought a number of transformative processes to humanity. Globalization has put shortened distances between continents, performing economical as well as political dynamics, which in turn had impact in the social and cultural scope. Besides the access to new forms of production and commodities, globalization has broadened access to new mediums of information and facilitated transitional fluxes. With this, processes of critical thinking have been appeared more frequently, thought the interconnection between groups, organizations, institutions and individuals.

Since the first decade of the 21st century, humanity has been going through significant transformation in what regards cultural identity and civil participation on political affairs. Recent libertarian movements, such as the “arab spring”, “los indignados” and the several “occupy” have encouraged new processes of discussion about democracy and the role of the estate as the one who regulates and perpetuates the status quo. In the field of arts and culture, one can observe the appearance of international programmes that foster visual as well as critical production, from art residencies to independent initiatives. Projects such as Transnational Dialogues appear as a tool for multidisciplinary, collaborative critical reflection between artists and cultural producers from several countries worldwide.

Given that China and Brazil occupy a central place in the agenda of the programme, it is relevant to reflect upon some similarities and disparities regarding social, cultural and political aspects of both countries. The space, its uses, accesses and regulations are one of the subjects widely debated during the “Brazilian Caravan”, which took place in February 2014, in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.

Space and the informal city

The favelas are one of the most common examples of informal urban organisation. In Brazil they are not only widely spread throughout the country’s large cities, but are also part of the popular imaginary of inhabitants and visitants of cities such as São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.

This organisation comprises an unique form of self-maintaining and regulation environment. Given the fact that formal law often neglects favelas, its inhabitants develop simple yet ingenious ways of surviving and running the space. The use of the space is a complex and intriguing issue in itself. Due to the high levels of violence, police brutality and lack of basic infrastructure, the laws of favelas are commonly established by the drug traffic. Therefore, a person who is not from the community in which the drug traffic operates doesn’t have free access to the space without an informal permission. This is usually guaranteed by knowing someone from the favela or going the to buy drugs, but it takes a while for the person to gain trust and be free to come and go as he pleases.

The space of favelas is an extremely complex space and has a pulsing visceral aspect. The side laws that orient the everyday life at these communities make them an intriguing and fascinating setting. The human aspect is fundamental in such scenario, as it is the force that builds invisible walls and produces the keys to open and close its gates. Such phenomenon apply a strong conceptual force the favelas, especially regarding the ideas of public space and private space, self-construction and self-maintenance. It builds a quotidian that function independently from that formally organised and institutionalized but that relates with it through social, political and economic interconnections.

The study of the informal cities and the formation of favelas are relevant to the debates occurred during the Brazilian Caravan, once they open discussion about subjects such as informal and formal economy, identity in the contemporary globalised capitalism, the formulation, structuring and management of independent cultural spaces and the uses and reclaim of public spaces.

The Chinese context

China is currently the second economy in the world and is known as “the world’s factory” for over decades. Despite its complex political and economical structure, the country has been opening itself increasingly to the international market. However, the Chinese government enters the international market in an aggressive way, but imposes strict regulations to the national capital.

Over the last decades, the country has been gaining considerable attention in the international contemporary arts scene. Artists such as Ai Wei Wei, Chen Xiaoyun, Yu Hong, Xu Bing, among many others, feature this recent and strong production, showing their work in events such as the Venice Biennial, The Documenta and the major international art fairs. This recent participation in the international industrial and cultural market, allied to the severe political regime, makes China a quite intriguing country for the critical assessments proposed by the visual art and art theory. In one hand, one can see a process of cultural miscegenation. On the other, Chinese citizens face a government that imposes restrictions, curtails speech rights and shortens the range of civil actions.

As far as it’s known, in China the government is absolute and sovereign, detaining full power over the space, whether public of private. The concepts of private and public space don’t fully apply in the practical everyday life of the country, once the feeling is that there’s no liberty of expression. If in one hand, in Brazil, we find a government that is functional (despite it’s many issues) in the formal city but impressively negligent to the informal cities, on the other hand the Chinese government is omnipotent, which doesn’t mean that there aren’t neglected spaces.

The dimensions of control in China extend to a level of complexity that transcends the tangible space. The use of virtual space is also heavily controlled. In 2011, the artist Ai Wei Wei was kept in custody for over three months, charged for irregular financial transactions. However it’s speculated that Wei Wei was held due to his political position. He produces works that defies the rigid political structure of China and the government feared that the artist brought the libertarian ideologies that inspired the Arab Spring to China. As a result, the Chinese State has increased the online censorship, taking a number of websites and pages down and abridging the right of speech from several Chinese citizens. It is possible to find images online under the searching terms “the great Chinese firewall”, showing censored web addresses and searching terms.

This authoritarian process brought up again the discussions about civil rights, both within the country borders and internationally. One of the aspects pointed out during protests and debates was the contradiction of the Chinese government, a great economical power that is also a gigantic oppressive machine. The political regime allows a greater marketing articulation, opening space for the private capital, but imposes heavy regulation rules. Yet, hinders intellectual and cultural movements that raise issues related to the functioning of society.

Nevertheless, such challenging setting is quite fruitful for artists, intellectuals and thinkers, who incorporates the issues to their discourse and foment the international debates about freedom, art and politics. The Chinese contemporary arts present a provocative, disturbing and subversive output. In the Brazilian favelas, the complexity of relations that run and characterizes the space also contributes to its cultural richness. Popular cultural expressions such as samba, the carnival and funk were born in deprived communities and were later on absorbed by the mainstream media in the country. Important contemporary artists such as Helio Oiticica and Cildo Meireles have shown the richness of the culture that comes from the “morros” (hills, where several favelas are formed in Rio de Janeiro). Both Chinese and Brazilian settings are full of contradictions, social and political tensions, but these build a unique foundation for the development of fascinating cultural forms of expression, that injects freshness into the contemporary information regarding arts, marketing, freedom, democracy and the role of the State.

Raphael Franco is a visual artist and educator. He has taken part in the First Caravan of Transnational Dialogues 2014.

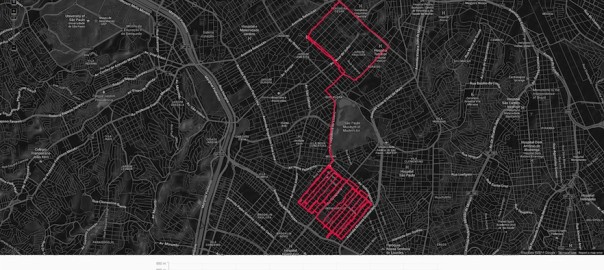

(Image on top: “Cicleline: Exploring Ortogonals”, 2014, Raphael Franco)