Collectives and Bottom-up Initiatives. Learning from the Examples in Brazil. An article by Iva Čukić, as published in the Transnational Dialogues Journal 2016.

The aggravation of social inequalities and poverty, and the rise of unemployment and existential uncertainty in Brazil, especially among young people, has driven various groups and individuals to seek niches beyond traditional social structures in the hope of discovering new possibilities and ways of (re-)action in order to achieve their desires and needs.

In the modern capitalist system, these actors do not have the same level of social and political power and influence, nor is there equal opportunities for involvement in decision-making processes and management of public resources and the city. What is particularly noticeable in Brazil, especially in Belo Horizonte, is the connection and gathering of different groups and individuals with the intention of creating new spaces and forms of sociability which are manifested through new forms of work and decision-making, self-organisation, temporary structures and activities.

In contemporary theoretical discourse, collectives and bottom-up initiatives are often discussed within the concepts of neo-Marxist theory, putting an emphasis on the concepts of the right to the city and everyday life, endeavouring to establish a new system of values, different to that of the dominant pervasive neo-Liberal paradigm. The idea behind such initiatives is opening up the opportunities to realise systematic change in city production by legitimising new social and cultural values, leading to establishing new urban relationships. The neo-Marxist concept of sociable space frames space as a result of social production and the expression of different social processes. Hence, the phenomenon of spatiality comes from specific (informal) social practices, and thus every society produces its own space.

Lefebvre’s observations through theory of production of space provide a specific way of interpreting and reading this collective practice. The author interprets the production of space through the levels of: (1) spatial practices (production, reproduction and the set of spatial characteristics that form society), (2) representation of space (symbols, meanings, knowledge and ideas), (3) representational space (lived experiences and lived space). In this sense, space represents a reproduction of directly endured reality, where social activity represents a major area of political struggle.

For Lefebvre, the nature of space is the key element in any process of transformation of social relations. He argues that the social and political nature of space in the context of social and economic change of urban development is at the centre of the political agenda. He believes that the operational and instrumental role of space can lead to a place of conflict and become a central part of political struggle. Therefore Lefebvre recognises the important role of the “place of conflict” in order to create spatial heterogeneity, through the redefinition of imposed vision and relationships, respecting the right to be different.

The right to be different is realised through spontaneous actions and activities; by practising everyday life that is contrary to the dominant paradigms of urban development. The collective bottom-up practices and initiatives in the context of activist practices and spaces for the community can thus be considered a form of rebellion and resistance to the repressive state apparatus and the logic of the real estate market, by the simple fact that they create autonomous spaces of everyday life.

These activist practices and spaces for the community are often associated with the concepts of temporary autonomous zones and the right to the city, drawing on the political ideas of Hakim Bay, David Harvey and Henri Lefebvre, as well as an entire list of ideas formulated around alternative economy, ideology and practice.

The political writer Hakim Bay is the author of the concept of Temporary autonomous zones (or TAZ), which has strongly influenced contemporary social movements. According to Bay, the characteristics of temporary autonomous zones are: (1) their temporary nature and limited duration; (2) their mobility, and ability to establish elsewhere; (3) their relative invisibility; (4) their spontaneity; (5) their network structure, which does not imply exclusively the use of information and communication technologies, but also networking and sharing experiences and knowledge that are crucial to their continuity; (6) their direct relationships, by bringing together individuals into groups, based on common interests and the principle of mutual assistance.

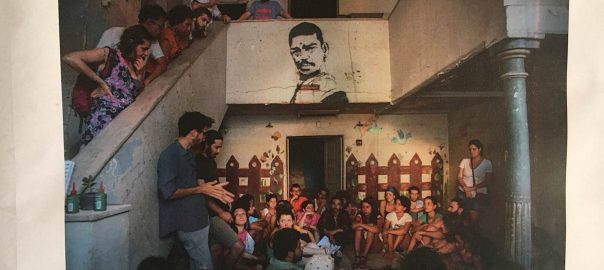

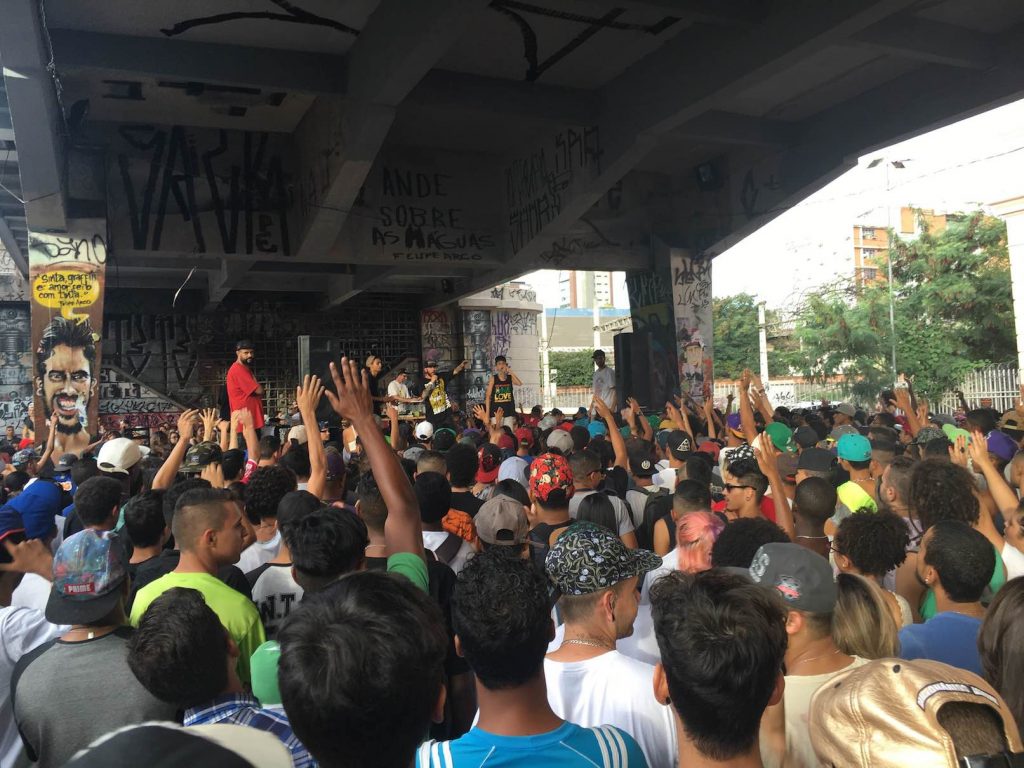

These characteristics described by Bay can be identified on the ground in the Brazilian city of Belo Horizonte, in the specific collective practices and initiatives of The People’s Horizontal Assembly (Assembleia Popular Horizontal), The Popular Committee for the World Cup (Comitê Popular Copa), Zero Tariff (Tarifa Zero), the MC’s Duel (Duelo de MC’s), The Common Space Luis Estrela (Espaço Comum Luiz Estrela), The Occupation Hope BH (Ocupação Esperança BH), Erro99, Occupation Tina Martins or Home for Women Tina Martins (Ocupação Tina Martins ou Casa de referência a mulher Tina Martins), to name but a few.

These initiatives are formed as activist practices and spaces for the community, or marginal groups. They represent a part of broader social movements, through which they articulate political action against the monopoly of the state and market, whilst also fighting against social inequality, and fighting for the rights of vulnerable and marginalised groups and individuals. By using and shaping the space to meet the needs of the community, these groups create autonomous spaces of everyday life, or spaces that Lefebvre described as lived spaces: spaces of new urban sociability.

Collective bottom-up practices and initiatives have far greater freedom in forming their own profile of space and functioning on the basis of preferences of people that use it, as well as being able to articulate the needs, interests and desires of the community. In this way, the community is formed through interactions based on common activities and recognition of the right to social and physical space.

Public space, and the activities that happen in it, represent the reflection of human life in the city. Thus, the nature of collective and bottom-up practices and initiatives in the public space of Belo Horizonte can be interpreted in several ways. The diversity of action and activities depends on the heterogeneous nature of their initiators, as well as the problems that they want to address, thus they can be interpreted as performative action (social and cultural), or as ideologically motivated action (political protest).

The aim of these various forms of collective practice, bottom-up initiatives or interventions in public space, is to provoke dialogue that can be viewed through creative improvisation and adaptation in space, or in the case of political protest, to encourage long-term changes in social and physical space. In reaction to the speculative activities in Brazil in recent years we have seen the manifestation of collective practices through political actions and expressions of protest from The People’s Horizontal Assembly, The Popular Committee for the World Cup, Zero Tariff.

These political and protest actions arise from imposed ideas, as well as ideas of the rights of citizens, which is reflected through the occupation of space and the transformation of streets and public spaces for a short period of time. For example, the ideological and political position of the actors involved in The People’s Horizontal Assembly is formed on the basis of principled commitment and moral conviction, as well as by recognising the phenomenon of civic awareness. Thus, this political movement, as a sign of protest, occupies public space in order to emphasise the negative impacts of great social inequalities and development through the market economy.

On the other hand, there are site-specific works, various forms of performative action and participatory forms of cultural and social activities which are developing tactics for the appropriation of public spaces, such as the MC’s Duel, The Home for Women Tina Martins and The Common Space Luis Estrela. This type of action can be seen as part of a wider phenomenon of DIY-philosophy, dealing with the city through the concept of production of the city according to the actual needs of their users. These examples demonstrate that operating in the public space contributes to strengthening the collective spirit, improving urban (public) space and making that (collective) space more sustainable. Following neo-Marxist concepts and theory of production of space, these collective practices and bottom-up initiatives are becoming, through their performative actions, central elements in the production of space.

Performative collective action and space thus result in a cause-and-effect relationship; mutually interdependent processes that mark everyday life. Hence, new urban sociability finds public space as a space of participation and debate on the creation of new possibilities, and the actors in these collective practices are in the process of (ful-)filling the space with new meanings and relations.

Regardless of the common ephemeral character of these forms of collective action and bottom-up initiatives, they can have a long-term impact on society by provoking dialogue on current issues about culture, society, politics, and urban development. A large number of different research studies are pointing to the importance of collective performative actions, collective and bottom-up initiatives, because of their tendency to turn towards the public sphere.

By practising different forms of collective actions, initiatives can form the space according to the actual needs of actors involved in the process of (self-)organisation by establishing their own system of values in their urban environment. Proponents of the neo-Marxist concept of the right to the city describe this right as the right to live in the city, but also as a right of citizens to defend the space and the city from repressive state or market apparatus. The concept of the right to the city makes visible the fact that the city is public and it represents the place of social interaction.

Thus, the given examples of collective and bottom-up initiatives show that local communities, activist and civil society organisations are occupying public space in different ways, emphasising their right to the city and everyday life, demonstrating alternative ways of managing and using space and the city. In that sense, the used and lived space becomes an ideological and political product.

Bay, H. (2003) The Temporary Autonomous Zone. New York: Autonomedia.

Brenner, N. (2000) The Urban Question as a Scale Question: The Reflection on Henry Lefebvre, Urban Theory and the Politics of Scale. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 24.2, 361-378.

de Certeau, M. (1984) The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lefebvre, H. (1968) Le droit à la ville. Paris: Anthopos.

Lefebvre, H. (1991) The production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell.

Lefebvre, H. (2008) Critique of Everyday Life. London/New York: Verso.

[All photos were taken by Iva Cukic during the Nomadic Residency 2016 that took place in São Paulo, Belo Horizonte and Recife]

Iva Čukić is an activist and architect. Her areas of research include public space, self-organisation, DIY philosophy and urban-cultural discourse. She co-founded Ministry of Space (Ministarstvo prostora), one of the first initiatives aimed at fostering citizens’ participation in urban development, initiating dialogue between citizens, social activists, urban developers, architects and city officials about the development of Belgrade and other cities in Serbia. She was a Fellow of Transnational Dialogues 2015-16.