Text written by Azu Nwagbogu for the exhibition Foam X African Artists’ Foundation, 19 May – 16 July 2017, at Foam Fotografiemuseum Amsterdam. Também disponível em português!

“If as one people speaking the same language they have begun to do this, then nothing they plan to do will be impossible for them.” Genesis Chapter 11 Verse 6

When was the last time you saw a leading African, a black person, in a fictional narrative in which the character is enhanced and inspiring? Perhaps in a comic book, or as James Bond, in a major television series, surely in the movies? While you search, I present you three young global leaders from Africa disrupting this narrative. Mũchiri Njenga, Kadara Enyeasi, and Osborne Macharia are rephrasing our contemporary reality through fictional narratives using lens-based media.

Kichwateli from Studio Ang on Vimeo.

For his short film Kichwateli (2011) (Swahili for ‘television head’), Njenga was inspired by the work of the African American science-fiction writer Octavia Butler. He also drew on poorly documented African achievements in biotechnology, astronomy and literature. The lead character, a young boy with a box television embedded gallantly on his head, is a seer sent from the future to prepare the minds of the people for the coming of a new epoch. He navigates the precarious streets of Nairobi transmitting information through the tube fused on his head.

Set in various parallel times and spaces, the short film speculates on the role of tradition and spirituality in a futuristic Africa. What role would the birthplace of humanity – Africa – play in what is widely predicted to be the next giant step in technological advancement – Transhumanism? The commonly held belief amongst transhumanists is that we will evolve into different beings with abilities so greatly expanded from the natural condition that they merit the label of post-human. This might sound ludicrous today, but no more ludicrous than any of the technological advancements that we enjoy today once seemed.

Osborne Macharia, too, has embraced such Afrofuturism with religious zeal and will have hour-long conversations about each of his fictional characters. His larger-than-life surrealist images are all conjured directly from his imagination. For example, his portraits of the Kipipiri 4 (2016) tell the fictional story of four wives of the Generals leading the Mau Mau uprising in then British Kenya. These women played key roles in the struggle by hiding food or information in the colossal and symbolic coiffure done on their heads as the day of the full moon approached. For Macicio (2015), he photographed men wearing eye devices said to be used during the Mau Mau uprising to see the enemies during nighttime.

As one can imagine, Macharia’s studio feels like a film set with his stylist, Kevo Abraham directing affairs while he daydreams in the corner. Macharia collaborates with models that are socially neglected or outcasts. It is an amalgamation of young, old, tall, and not so tall, albinos, all on set and in conversation. They have become his friends and companions. A great motivation for the series was Macharia’s dissatisfaction with accepted norms in music videos and fashion shoots. He wants to “prove that anyone can look beautiful and that we can all have power and influence, no matter your age or where you come from”.

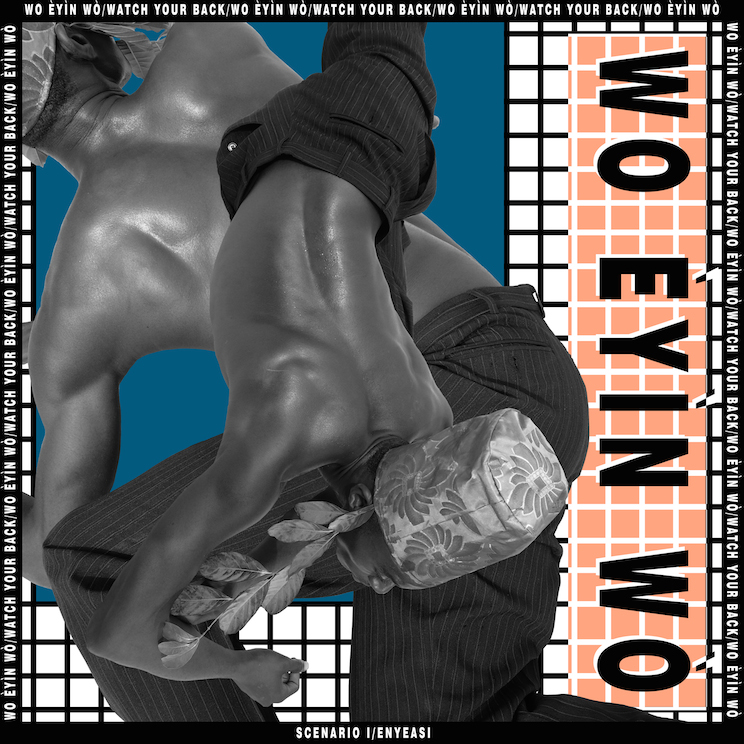

The careful (digital) curation of an alternative reality is also a primary concern of Kadara Enyeasi. He originally trained as an architect and fuses ideas from modern architecture into his digital collage series. Heavily inspired by Franco-Swiss master Le Corbusier, he adapts tools created by the modernist master as visual aids to orchestrate a fantastical universe. His male subjects twist and cavort; adopting sculptural forms. By shooting only male bodies he creates a dialogue challenging the anti-gay laws in his home country Nigeria. He combines his Afrofuturist aesthetics with a penchant for indigenous traditions such as Arodan. This is a Yoruba phenomenon whereby the subject (usually a child) is distracted (usually by the parents) by being sent out on errands that are unrealistic and unattainable. In the work of Enyeasi, this tradition becomes a sort of metaphor for Afrofuturism – the journey and not the destination is the essence of the story. In Scenario I: After the L’Ouverture the viewers’ gaze is constantly diverted and sidetracked by subtle references to various cultural traditions that seem to be irreconcilable. Enyeasi’s creations are emblematic of his generation that refuses to be tagged by simplistic labels. He fuses African dialectics with ideas from western modern and contemporary art and makes it his own.

What inspires these artists’ anxiety and simultaneous fascination for the future, and why has Afro-futurism captured the imagination of several young photographers working in and from Africa? It is really simple: dissatisfaction with our current reality. The future has arrived and it has not lived up to its promise. We pine for the past where we yearned for the future. Relentless capitalism, climate change, terrorism and rising costs induce reduced expectations for the coming generation. Perhaps for the first time in recent world history the next generation cannot look forward to having as many essential environmental and material options as their predecessors. We are inundated by facts but we do not have the truth – the emotional truth – that exists only in sentimentality and fiction. There are several ways to tell a story, as there are ways to obfuscate the truth and lie about it. But there is no lying about the future – it has not happened and we therefore cannot prove otherwise.

If African creative talent must change the vision of the continent then we must embrace the same tools that were used to perpetuate the false preponderant narrative. Film, photography, literature and music have the power of expression through contemporary art and this exhibition at Foam is a synesthetic expression of these faculties. Photography and digital technology have united to give the world a new universal language that is not obscure, but is understood from tribe-to-tribe, region-to-region, from Africa to Asia with social media playing a key role in catalyzing this aspect of visual literacy. Our achievements, especially in communication, over the last century defy a previously prevailing logic, and now humanity can finally unite under the same global language. If the scriptures are to be believed this is the only thing that has held man back and now we can finally build the metaphorical tower to the heavens. The language of zeros and ones that constitute basic computer language has enabled scientists and artists alike to imagine a future where man is either able to make his own god or is so powerfully enhanced that he feels like he is a god. But the relentless (Catholic) veneration of whiteness that has long dominated visual culture is experiencing restive, darker, emulation in Afrofuturism. We should all be believers.

[Cover image: From the making of Kichwateli, 2011 © Studio Ang – http://studioang.tv/enkang/the-making-of-kichwateli/]